News 116, From Singapore to Vietnam, Interview by Olivier Souquet

116

Olivier Souquet conducted for the French online newspaper,“ le journal de l’architecte”, a long interview of Jean François Milou, which was never traducted or summarised in English.

https://chroniques-architecture.com/de-singapour-au-vietnam-entretien-avec-jean-francois-milou/We give in this news the full content of this interview:

Conversation

Olivier Souquet: “Jean‑François Milou, I have been wanting to have this conversation for a long time. Ever since we have been exchanging about our respective practices in Southeast Asia and Vietnam, I have wanted to ask you about how you see the current architectural production in France, a country you left professionally almost fifteen years ago, and where you built some very fine projects.”

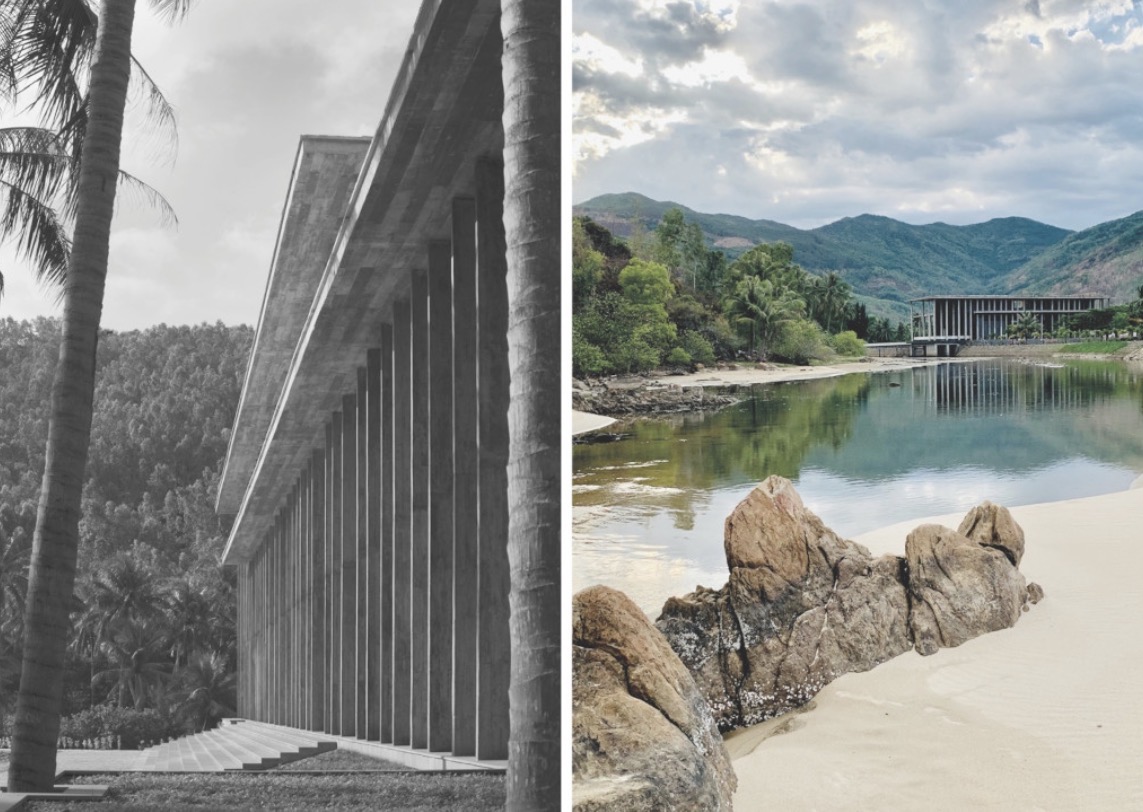

Jean‑François Milou: Olivier, we’ve already spoken about this: in Europe we are witnessing a drift of the architect’s profession, which is tending to become nothing more than a small adjustment mechanism for the economy. By giving architects a social, then an environmental mandate, some people thought they were granting the profession great nobility, but in fact everything essential has been taken away from architects. The multidisciplinary evolution of architecture into a discipline “at the service of” something strikes me as absurd. If we try to define architecture, we should perhaps begin by saying what it is not. Architecture is not a discipline for solving functional problems of the economy. Architecture is not a discipline that advances step by step on the basis of quantified evidence, following protocols formatted by economists, sociologists, environmental experts and politicians. Architecture is, as it has always been, a work of complex geometric composition applied to situations and landscapes. And, just as we have seen the disappearance of religious community in the West, we are now witnessing the disappearance of a “geometric community”. The sociologist Hervieu‑Léger has shown how religious feeling has left the great institutions fragmented, reinvesting itself everywhere in individual “boutiques” and universes (yoga, wellness, meditation, etc.). The same can be said of the “first collective geometry”: it has withdrawn from the shared architectural field and fragmented everywhere across Europe, reinvesting the realms of tourism, design, advertising, cinema, and so on. If you ask me, as an architect, to talk about what I do, I probably won’t manage. Only by looking at the projects our studio has built over about thirty years can you really find answers to that question. It is worth noting, though, that since 2009 we have quite clearly shifted the centre of gravity of our work towards Asia. It is true that tropical Asia allows us to juxtapose a rich architectural work through sculptural elements and very fine structures, placed in extraordinary landscapes. Working in societies that still maintain living traditions (family, age hierarchies, craft work) encourages a certain classicism in how the whole is resolved, and an intuitive experimentation in how all the details are resolved.

Olivier Souquet: “Yes, I agree with you: speaking about beauty is almost inaudible in France. Architects are constantly justifying what they do, and that is certainly not the right way to enhance their own value. To speak of emotion, for an architect, is hard; dissecting why we like things is not simple. The silence of Barragán’s spaces cannot be explained, and the way he frames landscape is almost mystical!”

Jean‑François Milou: Architecture is something both fundamental and very traditional, and it is difficult to explain why it works. It seems to me that architecture is very late compared to musical composition, to the history of music, harmony and counterpoint. Look at how classical and contemporary music have managed to hold their ground in this world, while architecture struggles to exist and must constantly explain itself. I am inclined to say that architecture is the crossing of a collective geometric tradition, which exceeds the architect, with an emotional intelligence applied to landscapes and situations. The soul of a composition is out of tune with language: a fountain set down here, a wall composed to this height, a path that meanders—these things are simply established, they are not up for debate.

Olivier Souquet: “Your architecture is written; you develop a vocabulary, a style, even a particular colour in relation to the ground and to nature. Can you say more about the tensions and connections you bring into play in your projects?”

Jean‑François Milou: I am inclined to say that we have forgotten what gravity is. That is to say, mass and weight, which are forces that are constantly at work. In our projects, we work to bring the density of design back downwards, to bring shadows and contrasts back to the ground. Likewise, we try to draw warm colours towards the ground and let cool colours escape towards the sky. Inside, when we design furniture, we avoid drawing pieces taller than about one metre twenty. I think this is an intuitive visual accompaniment of the force of gravity in composition. In our work you will find the repetition of recurring elements: fine columns, screens that filter the light, walls with no windows. It is a work of reconstructing a geometric vocabulary, rules of composition, leitmotifs, assembly details, principles of construction. But if I had to say what we do, I would say that we try to install, in our practice, a way of doing things, a specific style.

Olivier Souquet: “Yes, it is with a vocabulary that one can compose, like a book composed of letters that form words, then sentences and chapters. You need coherence, the effort to maintain a vocabulary, especially in Vietnam. Can you talk about your fascination with archaeology?”

Jean‑François Milou: My archaeological studies shaped me a great deal. I became interested in the emergence of collective geometric systems in the first great empires on the one hand, and in the appearance of the first cities on the other. Ever since that time, I have considered archaeology to be the avant‑garde of architectural research. Like you, I work much more on the articulation of projects with the ground (materialism, classicism), through the creation of a massive podium that can withstand time, on which the pavilions change and the secondary construction turns over. Every quality project dreams of its own archaeological form.

Olivier Souquet: “If we look at Indian cities and their powerful geometries, their sophisticated water management, we see a great history of the human projection of geometry onto the ground, completing natural geography and topography. Like you, I think human geography inscribes itself into geography; it is from that entanglement of geometry and geography that density, reason, history and fleeting emotion are built. Architecture is bound to the place, to the site it irreversibly transforms. But let’s return to the essential: intuition. How do things come to you?”

Jean‑François Milou: I was also influenced by my interest in haute couture, through a great‑uncle who was a musician, a financier and a close friend of Cristóbal Balenciaga. Fashion shows on stone plinths in moonlight strike me, intuitively, as a perfection of civilisation. I told you that the architect’s task is to cross a geometric tradition with an emotional intelligence applied to landscapes and situations.

Olivier Souquet: “What you describe, and what comes up often, is the gap between analytic and synthetic thinking, this divergence between emotional and analytical intelligence. The architect would be torn in the middle of all that; emotionally sensitive, he stands at the centre of so many coexisting intentions. A building is the tensioning of forces, of technique, of weight and transparency, of logics and costs. And in all this work, we may have forgotten to speak about the essential?”

Jean‑François Milou: When you use your emotional intelligence, you have to know how to forget what comes from analytic intelligence. That is quite hard to get across in a technical and economic world in which everything is governed by the analytic approach. By agreeing to develop according to analytic criteria (impact studies, quantified tables of criteria, diagnostics…), architecture becomes a secondary discipline of the economy. You can see this today in Europe, where architects are trained to justify their decisions based on criteria derived from economics: performance tables, carbon footprint, environmental performance, labels. Yet landscapes and human situations are too complex to be approached by analytic intelligence alone. In a landscape, without intuition, everyone is lost; no animal can survive in its environment without it, no athlete can win a match without it, no fashion can appeal without it.

Olivier Souquet: “I am certainly not going to contradict you… You mean that inclusive thinking is killing architecture, and that we have gone astray into a world where the architect must always justify everything, unlike an artist. At the same time, we are asked to constantly reinvent everything, to be innovative…”

Jean‑François Milou: That is partly true. For example, the sculptor Giacometti is an artist who always did the same thing, and no one ever asked him to explain his repetition. His work is enormous; his contribution—devoting a lifetime to simplifying and expressing one single thing—is immense. It is like Mies’s work, where the unity of style reached a sculptural dimension. Artists and animals can resolve very complex questions at extraordinary, inexplicable speed. That is almost certainly what is being asked of us, and we have somewhat forgotten it. You often speak of “modern meditation” in your buildings, and there is also the question of style and repetition that we find in contemporary music. Yes, it is the elaboration of a style that interests me. I see that in France and in Asia alike I have circled around the same issues, composing with the same architectural “ideograms”. I have always tried, within lush landscapes where wind and light move freely and where life, rhythms and traditions unfold, to install walls without windows, monumental screens, rows of almost vertical fine columns, glass walls without visible structure, wide steps laid out horizontally on the ground. It seems to me that Nietzsche is right when he says: “Good is something one can see oneself repeating an infinite number of times, whereas evil is an act one cannot see oneself repeating an infinite number of times.” It seems to me that an “architectural style” is the setting in place, through work, of elements—fine almost vertical columns, light‑filtering screens, blind stone walls, glass walls, etc.— that one can imagine repeating an infinite number of times.

Our website is not designed to work on mobile phone in the horizontal “landscape format” , please switch to the vertical “portrait format” when you want to access the studioMilou website on a mobile phone.

The StudioMilou team